By : Zafarullah Khan

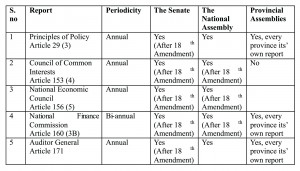

The 18th Constitutional amendment brought about monumental shifts in Pakistan’s federal architecture and introduced new divisions of power between the federal and provincial governments. Now it is constitutionally obligatory for the annual reports of Council of Common Interests (CCI), National Economic Council (NEC), and bi-annual reports of National Finance Commission (NFC) to be prepared and laid before both houses of Parliament for debate and discussion. These reports covering the political and fiscal aspects of Pakistani federalism can be described as new instruments of democratic-parliamentary accountability and transparency.

Before the 18th amendment, there was an explicit constitutional requirement to prepare separate federal and provincial reports on implementation of the Principles of Policy, in the federation and in each province. Earlier, this report was only to be laid in the National Assembly. The amendment has made it mandatory to present this report on implementation of the people’s part of the constitution in the Senate of Pakistan as well. The case of the Auditor General’s annual report is similar as it is now mandatory to lay it in the Senate along with the National Assembly. One can regard this development as an attempt to expand oversight role of the Upper House that otherwise does not have financial powers.

Reports to be laid before the Parliament:

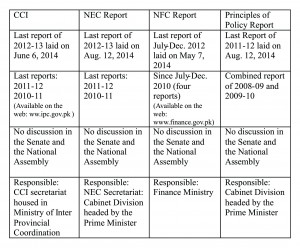

Two years after the adoption of the 18th amendment in April 2010, these Articles remained non-operational due to traditional bureaucratic lethargy and a culture of non-compliance vis-à-vis the Constitution.

On January 18, 2012 Senator Prof. Khurshid Ahmed of Jamaa’t-i-Islami moved a different kind of Privilege Motion that read; “In April 2010 the 18th Amendment became part of the Constitution. After nineteen months of this, no report has been presented in the Senate. This is a flagrant violation of the privilege of the Senate. The Senate should seriously consider censuring the government on this failure and demanding immediate presentation of all the constitutionally stipulated reports.” The articulation ‘privilege of the House’ was innovative as majority of the privilege motions often pertain to individual-member privileges.

Following this, important debate on constitutional institutionalism took place that upheld the status of Council of Common Interests and National Economic Council as not merely government institutions but as independent constitutional bodies. The direct benefit of Senator Khurshid Ahmed’s move was that these bodies and the government started laying all required reports in the Parliament from March-2012 onward. However their periodicity is still disturbed.

Moreover, these reports have failed to arrest the attention of mandate bearers, the media or the public. There was no follow-up debate or discussion in the Parliament, the media failed to take up the task of critically dissecting and examining these reports and the civil society failed to seize this opportunity for reflection on the performance of these institutions. In this way, these major instruments of democratic accountability remained underutilized.

Culture of Constitutional Compliance:

The Article 160 (3B) says: The Federal Finance Minister and Provincial Finance Ministers shall monitor the implementation of the Award biannually and lay their reports before both Houses of the Parliament and the provincial assemblies. One interpretation of the said Article, which talks about ‘their reports,’ could be that there have to be separate federal and provincial reports. But only combined reports have been produced and laid before parliamentary institutions at the federal and provincial levels.

A study conducted by the Centre for Civic Education Pakistan on Adherence to Principles of Policy in July-2014 reveals that the provinces of Sindh and Balochistan have not produced a single report on the implementation of Principles of Policy since 1973 when it was made constitutionally mandatory to do so. In Punjab the last report covered a period up to 2010 and in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa up to 2011. The provincial assemblies where these reports were laid also failed to devote a single minute for discussion and debate over these.

This research also confirms that government officials are rarely given any focused training on how to prepare these reports in a creative way, to make them more coherent and informative. Therefore most of these reports continue to use traditional bureaucratic templates which are unable to capture the interest of readers and convey the broader picture. Even in these times of e-governance, not all of these reports are available to citizens on relevant official websites.

Discussion on reports:

The Constitution of 1973 asks for discussion on the federal and provincial reports on Principles of Policy in their respective parliamentary forums. The respective Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in the National Assembly, the Senate and all the four provincial assemblies also provides for discussion on these important reports. The Rules of the National Assembly (Rule 180) and the Senate (Rule 157) ask the Speaker and the Chairman Senate to fix a day for discussion on reports. The minister concerned is entitled to make a brief statement to explain salient feature of the report and the members of these Houses are entitled to express their opinions, observations and recommendations through a resolution.

A similar practice is envisaged in the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business for the Punjab and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa assemblies. In Balochistan, the report is referred to a committee which is expected to come-up with recommendations. In Sindh, any member can serve a notice within six months of laying of the report for discussion.

The federal and provincial legislators must understand and operationalize the spirit behind the constitutional clause that calls upon institutions to prepare reports and for legislators to discuss them. This is essential for improving the quality of reports produced, and giving them their due place as democratic instruments for accountability and performance review. It is only through these measures that these constitutionally mandated instruments can be used to strengthen democratic culture and improve performance.