Jami Chandio

While public sector institutions in Sindh in general remain deplorable, basic education is on the verge of obliteration putting the future of the province at stake. In the 21st Century which will be the century of competition and in turn of merit and skill, no nation or society can envision development without education. I call what has taken place in Sindh, “the evolution of annihilation”.

According to the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2012, there are 44000 primary, 5000 middle and secondary schools in Sindh; while the number of enrolled students aged 5-16 is approximately 4 million. The report informs that the 66% students who have passed their third grade are not able to read even in their mother tongue; 78% of those are not able to solve addition and subtraction questions of simple arithmetic.75% of the students from government schools are unable to read a single sentence in English language. This poor condition is of the students aged 5-16, as majority of the schools does not have proper education; on the other hand, over 80% of primary, secondary and college teachers are unable to write in English.

Sindh’s current Minister of Education Nisar Ahmed Khoro admits that primary education in Sindh is at the verge of devastation; in this way it is a slight improvement from the stance of the previous minister who did not even admit that education in Sindh is in a bad state. Certain steps taken by the current minister such as reviewing the curriculum are reflective of the minister’s limited commitment towards the improvement of the quality of education but long-term strategy is still missing.

Article A-25 of the Constitution ensures compulsory and free primary education to children aged between 5-16, while Articles 37-B and 38 of the second chapter of the 1973 Constitution, also guarantee free basic education. The Article 26 (1) of the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights guaranteed (in 1948) that every human has right to basic education. Article 28 of the Universal Charter of Children’s Rights in 1989 accepted that all children have right to basic education. The second target of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs designed in April 2000) include basic education for 100% of the world by 2015 but this target remains unachievable in many parts of the underdeveloped world such as Pakistan.

The reason for the deterioration of education in government schools in Pakistan, especially primary and secondary education, is that the standard of educational expenditure set by the UNESCO is minimum 4% of the GNP, but Pakistan during last 66 years has been spending on an average only 2% of the GNP. According to that even the poorest countries are far better than Pakistan vis-à-vis education; Sri Lanka and Bangladesh are especial examples in this regard in South Asia. The national educational policy designed in 2009, suggested that the 7% of the national income/GNP be spent on education, but this has failed to materialize in a country that prefers to spend resources on defense instead of education and other development projects. Education, especially for the poor has never been the priority of the state.

In 1951 there were 2.0 million children deprived of education; while according to the 1998 survey that number exceeded to 5.5 million. In Pakistan 5.5 million children aged 10 years are not able to read and write even in the 21st century. 52% girls between the ages of 5-16 are not enrolled in schools, and resultantly 67% of women are deprived of ability to read and write. This example depicts the alarming picture of the state of education from the inception of the country to-date.

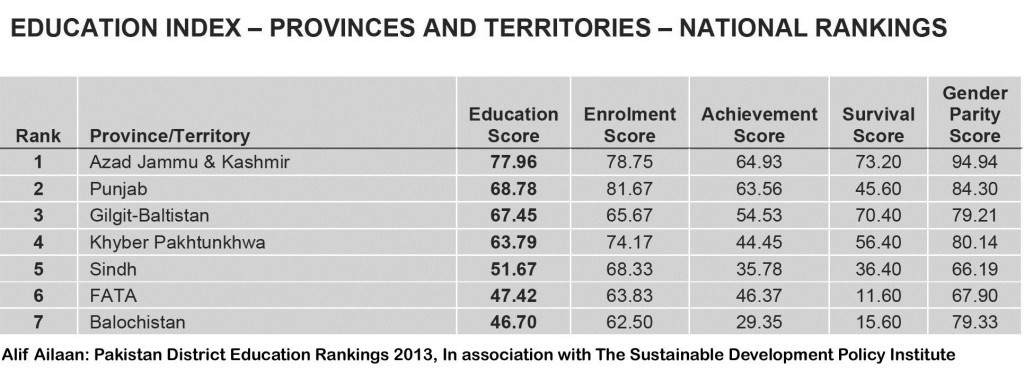

Primary and secondary education in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has improved comparatively, while the condition in Sindh, Balochistan, Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and Gilgit-Baltistan is the worst. The tragedy is that Sindh’s education was the best among all the provinces in the country at the time of partition and remained the same till 1960s, which is now almost at the parallel status to Balochistan, FATA and Gilgit-Baltistan.

There are total 49000 primary and secondary schools in Sindh, out of which approximately 18000 are defunct. Most of those are used as go-downs and get-together places of local influential landlords. The television and newspapers have been showing pictures and documentaries on the schools that have turned into stables for donkeys, horses and other domestic animals. There are 1, 46000 teachers of primary and secondary schools; according to a survey, over 50,000 of those teachers never come to schools; they get their salaries by bribing the concerned authorities.

According to the government’ statistics there is 55% literacy rate in the urban areas, while in the rural areas it is 42%. However, the fact is that 39% out of 5-16 year old children go to government schools. Sindh is the only province of Pakistan where 21% (134 Billion) out of the province’s total budge (617 Billion) is spent on education. After the18th Constitutional Amendment education now is a provincial subject; nonetheless, in Sindh only 4.2 million children are enrolled into schools out of the total number, which is eleven million. There is no adequate space in the government schools to accommodate the remaining 7 million children, which the Article 25-A of the Constitution ensures.

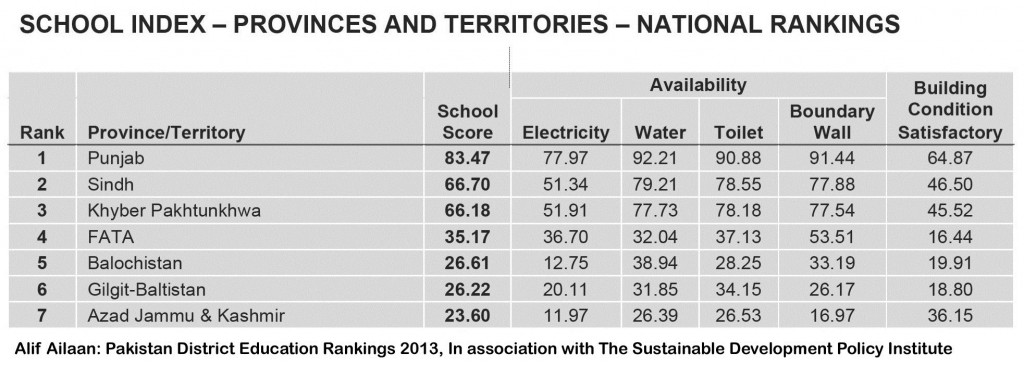

However, there are several other important dimensions of the issues of education in Sindh. For example why would parents send their children to schools where quality education is not imparted in word and spirit? According to the government’s figures there is no electricity in 24000 schools of Sindh, 10,000 schools do not have boundary walls, and 15000 schools do not have washrooms, and 20,000 schools lack drinking water. According to another survey 19% of the school buildings in Sindh are in disrepair and are a permanent danger for children. 58% schools require repair, most of which are turning into falling structures. Another dimension of this issue is that why would parents send their boys and girls to such schools? Reputable economic expert and Nobel Laureate Dr. Amartiya Sen has highlighted four standards in his thesis, without which parents and especially poor parents cannot send their children to schools: first, the schools should be near the homes of children, secondly, there should be free quality education, thirdly schools should be secure, fourth education must offer children a better future. If we look at the education of Sindh according to these standards, we would learn that there is no capacity of the Sindh government to give free and quality education to 11 million children, nor would the parents agree to send their children to schools with the problems discussed above, no matter what guarantees are ensured by the Constitution of the country.

A research report of the DFID (AlifAilan Project, in collaboration with Sustainable Development Policy Initiatives-SDPI)—conducted by a number educational experts and university academicians—has analyzed condition of education in Pakistan from various dimensions including statistical data of education in the country, provinces and districts. Findings of that report indicate a gloomy and forlorn picture of education in Sindh. For example country wise classification and educational index the educational score of Sindh is 51.67 %, admission of children score 68.33 %, success score 35.78 %, and survival score is 36.40 %. It means the drop-out ratio of students after admission is that it drops from 86.33% to 36.44%.

In the educational index Sindh is only better than Balochistan and FATA, while lags far behind Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

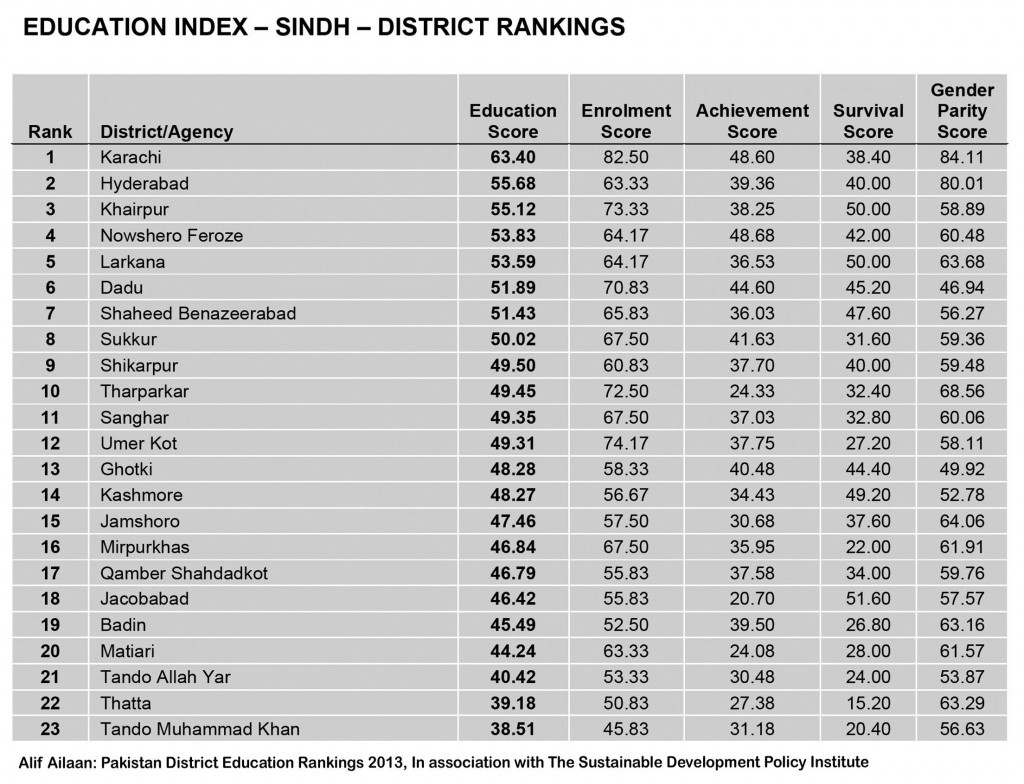

In the same country-wise report the district wise index is also declared, which is more alarming; according to which Sindh’s largest city Karachi too stands at 56 number out of Pakistan’s 141 districts. While the standing of the other districts of Sindh is like this: Hyderabad at 73, KhairpurMirs’ at 77, NaushehroFiroz at 80, Larkano at 81, Dadu at 88, Nawabshah at 90, Sakhar at 98, Shikarpur at 101, Tharparkar at 102, Sanghar at 105, Umar Kot at 106, Ghotki at 110, Kashmore at 112, Jamshoro at 116, MirpurKhas at 117, Qambar-ShahdadKot at 119, Jacobabad at 120, Badin at 122, Matiyari at 135, TandoAllahyar at 130, Thatto at 133 and Tando Muhammad Khan at 134 number. According to this survey not a single district is included in the list of the first 50 districts of the country, while the 15 districts of Sindh are categorized as the worst districts in country’s educational index.

According to this survey report, in country’s school index, out of 144 districts Larkano stands at 42, Karachi 44, Hyderabad 45, Sakhar 56, TandoAllahyar 58, Qambar-Shahdad-Ko 60, KhairpurMirs’ 65, NaushehroFiroz 68, Jamshoro 70, Shikarpur 72, Nawabshah 77, Sanghar 80, Ghotki 82, Tando Muhammad Khan 83, Umar Kot 87, Dadu 91, Badin 93, Khairur 98, Tharparkar 117, Jacobabad 125, Kashmore 127, and Thattto at 140 number. While in Sindh’s provincial index Karachi stands at number 1, Hyderabad 2, Khairpur 3, NaushehroFiroz 4, Larkano 5, Dadu 6, Nawabshah 7, Sakhar 8, Shikarpur 9, Tharparkar 10, Sanghar 11, UmaarKot 12, Ghotki 13, Kashmore 14, Jamshoro 15, Mirpurkhas 16, Qambad-ShahdadKot 17, Jacobabad 18, Badin 19, Matiyari 20, TandoAllahyar 21, Thatto 22 and Tando Muhammad Khan are at 23 number.

The statistics mentioned above portray a horrifying educational scenario in Sindh, it is unbelievable that this is the condition of education of the province, where 21.8% of the budget (134 Billion) is spent on education. The Minister of Education Mr. Nisar Ahmed Khoro told in an educational conference in Hyderabad organized by Awami Jamhoor Party that 118 Billion out of 134 Billion go directly to the salaries of teachers, educational officers and administrative expenses. The budget indicates to the shocking fact that the whole system is not for imparting education but fostering un-deserving teachers and filling in the pockets of corrupt officers. If we divide total expenditure of education with the number of enrolled children, we would learn that even in this corrupt educational system the government ostensibly spends Rs. 2500 per month per child. While, surprisingly, in India the government spends just Rs. 16000 annually on each child, and provides free education and meal to 12 million children. This policy has increased 22% of school enrollment in a decade; why could not we get the same target despite spending 30,000 annually on each child.

This appalling condition of education in Sindh even in the 21st century indicates towards a bleak picture of the future of the province. The upper and upper middle class families can afford educating their children in good private schools; the bigger chunk of those children would definitely see their future in developed countries instead of serving their own country. While the majority of the population’s children are destined to stay deprived of even basic quality education. Recently Commissioner of Hyderabad district Mr. Jamal Mustafa Shah has started scrutiny against absentee teachers by regular visits of the officers; similarly like the dutiful officers, responsible people from media, civil society and political parties can begin an effective campaign to address the issue. Every individual and institution that stands responsible for the downfall of education in Sindh, is a national culprit; be those representatives of the government, or corrupt bureaucracy and incompetent or absentee teachers.

No qualitative change is possible in Sindh without educational revolution. If the incremental deterioration of education of Sindh continues, where would it lead to the province? All those individuals and responsible citizens of our society, who have failed to give this issue required significance and could not play a vibrant role also share a portion of responsibility in this crime. I think it is a crucial time to take up the issue of education with required seriousness and responsibility, and political parties, the media and entire civil and collective society must play their respective roles in this regard.

[Author is renowned scholar, writer and activist, currently working as executive director Center for Peace and Civil Society]