Dr. Saeed Shafqat

Democratic systems around the world are under duress. Pakistan is no exception. Let me identify three trends that are reshaping the functioning of democracies and the parliaments.

Firstly, in recent years, democracies such as the UK, the European Union, India, Turkey and even the United States have witnessed major socio-political upheavals. There is a resurgence of a ‘populist upsurge’ both within society and at the leadership level, which has resulted in socioeconomic and political inequalities. Thus, democracies are at risk from populist leaders and movements, which are increasingly anti-democratic, anti- pluralist and parochial.

In Pakistan we are also witnessing an authoritarian streak. A wave of religious pugnaciousness, rising inequalities and injustices is tearing apart constitutional, liberal and democratic values. This turbulence has cast aspersions on the credibility of the parliament. Consequently, state-society relations have deteriorated and citizens have little trust in their elected public officials.

Second, technological innovation and the rise of social media, have transformed public discourse across states, nations, and societies. These platforms are bringing in numerous views on a broad range of socio-political issues. Yet designing legislation and public policy is a function of the parliaments. Increasingly the legislatures are confronted with striking a balance between constraining the surveillance functions of the State and protecting civil liberties of the citizens. Pakistani parliamentarians must monitor and learn from this emerging trend.

Third, over the past two decades, Pakistan’s involvement in combating the Global War on Terror coupled with the insurgency in Indian held Kashmir has kept Indo-Pakistan rivalry simmering. This has enhanced the counter-insurgency and counter- terrorism capacity of the Pakistan military and that has led to deepening of the Military’s entrenchment in Pakistan’s political system creating a semblance of political order, which is not akin to democratization. Conversely, the parliament has abandoned its key functions of consultation, negotiations, compromise and consensus building. There is a growing perception that the parliamentarians had an opportunity to strengthen the parliament, enhance its legislative capacity and streamline its oversight functions. However, they did not show commitment and integrity towards strengthening the two pivotal functions of the parliament: regulation and oversight. In addition, they could not protect citizens’ rights and strengthen welfare functions of the state with vigor and conviction.

Post 1971 Pakistan witnessed ten parliamentary regimes headed by civilian political leaders. During the years of parliamentary rule between 2002- 2020, the National Assembly and Senate sessions have not only gradually declined, but their legislative performance has also been dismal. For the past decade Pakistan sustained elected regimes led by one political party or the other. This could have been an opportunity for the political parties and their leadership to establish the sanctity and supremacy of the National Parliament as the supreme law-making body of the country.

Having passed the 18th Amendment adroitly, they have shown lack of ownership and commitment of purpose in pursuing and seeking its implementation across provinces. It is disappointing that parliamentarians have made little effort to consult, debate, bring to attention issues like seeking improvements in the 18th Amendment, such as climate change, curbing religious militancy, addressing youth bulge, improving human skills, etc.

The foundations of democracy and representative government are built on acceptance of rule of law and justice, irrespective of caste, creed and religion. Favorable disposition of these factors brightens prospects of robust legislatures and democratic development. Democracy thrives on competition, fair play and encourages merit. ‘Spoil’ system or distribution of rewards—i.e., extension of patronage to supporters of a political party is one important aspect of the democratic process. The expectation is that when in power, every party will implement the promised policies. In order to do so it relies on political activists and ideologues. Thus, for political parties, patronage system and parliamentarians grow side by side. Importantly, electoral process forewarns political parties not to obstruct merit, achievement, orientation or the citizens’ right to compete for and advance their interests. Among the people of Pakistan, aspiration for democracy and elected government is strong, but pro-democracy groups are few. Political parties remain glued to dynastic leadership, which pauses democratic dispensation and organization.

Obsession with authority and executive superiority is so ingrained that upon joining the parliament, parliamentarians support policies that strengthen authoritarian attitudes rather than promote democratic norms, values and respect for law or tolerance for dissent and political opposition (for example, the case of National Action Plan 2014, military courts and militancy).

Strengthening Parliament entails deliberating on policy issues, harmonizing competing interests through conciliation and consensus. Unfortunately, this process has been swapped by confrontation and blame game eroding its credibility. In a parliamentary democracy, the elected leaders are expected to synchronize the expectations of their support groups and others.

The Pakistani experience reveals a two-fold dilemma. First, a disharmony between the political leadership’s professed democratic creed and a strong tendency towards centralization, authoritarianism and exclusionary policies within the parliamentary practices. This conduct has impaired the credibility of the parliament. Secondly, political leadership in Pakistan reveals a management dilemma. On the one hand it aspired, and in some cases, struggled to restore democracy, espoused greater participation of masses into the political process, promised to build constitutionalism, promote pluralism, and ensure provincial autonomy. Yet in practice it favours a dispensation towards autocratic tendencies. For example, after the adoption of the 1973 Constitution, the civilian regime promulgated amendments restricting freedom of press, judiciary, and freedom of religion.

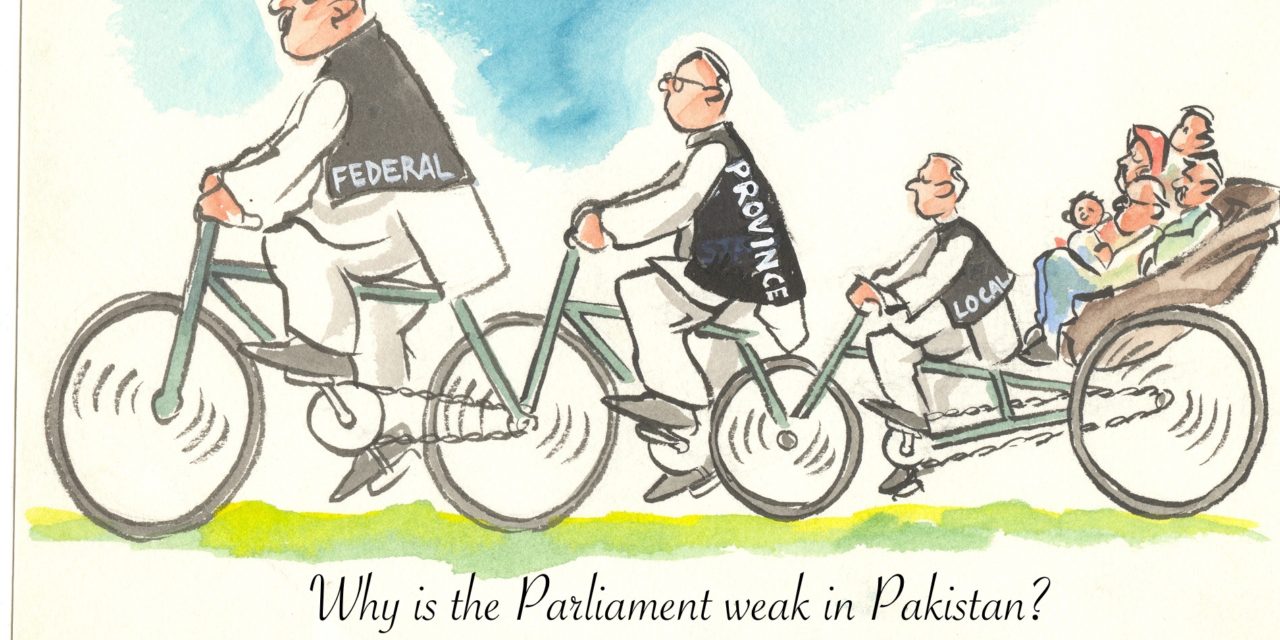

Similarly, adopting the 18th Amendment in 2010 enhanced provincial autonomy, declaring local government third tier of the constitution and devolving 17 social sector ministries, and yet within weeks the PPP regime created federal ministries via executive orders to constrain provincial autonomy.

In the foregoing analysis, some of the causes that restrain our parliamentarians from strengthening the parliament and establishing its supremacy have been identified. To remedy the issue, the following few steps are suggested.

- Streamline the Committee system. Empower it making its role substantive in framing laws, thereby reducing reliance on Executive orders and Ordinances.

- Enhance and regulate the Inter-Provincial Coordination Ministry’s role in developing harmonious relations with the Provincial Legislatures and Secretariats.

- Regulate Council of Common Interests (CCI) meetings, strengthen its secretariat and streamline agenda setting. Provincial legislatures and provincial bureaucracies should be strengthened, making CCI the pivot of Federation and federal policies

- A committee promoting coordination and reform among the political parties, which includes members of academia, labor unions, and women and youth organizations should be created.

- The Pakistan Institute for Parliamentary Services (PIPS) remains a good initiative but has become another bureaucratic structure so there is a need to energize its research capacity, legislation drafting, data collection and policy relevant professional skills.

[Dr. Saeed Shafqat is Professor and Founding Director of Centre for Public Policy and Governance at Forman Christian College (A Chartered University), Lahore]